Post-Election Data Download: Narratives About Democrats

This post is the third in a series that will examine the election and attempt to answer questions we have been asking internally and fielding from friends, colleagues, and allies. Please don’t hesitate to contact us with additional questions or input.

We’ve been looking at a few of the dominant narratives you may be hearing about the election. Previously, we examined the ideas that there was a “Trump surge” on Election Day and that Trump was the change candidate for 2016 to Obama’s 2008.

Today, we address a couple of narratives about Democratic voting behavior and the future of the Democratic party.

Black voters failed to turn out

We have been hearing some reports of this since early voting began, but we don’t yet know. We can’t measure this until we have better data—the first set of which will come out in the spring (of 2017), in the form of the American National Election Study.

What we do know is that, following Shelby v. Holder, the U.S. Supreme Court decision that effectively gutted Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, many states have been changing their laws or practices in ways that depress or suppress Black/non-white registration and turnout, whether through Voter ID laws, establishing fewer and less convenient early voting stations, or purging voter rolls.

There was a Latino surge

Like Black turnout above, it’s going to be a few months until we have strong data on Hispanic turnout in the 2016 election. Between a growing Hispanic American population and incendiary comments about Mexicans from Trump, many expected there to be a surge in Hispanic turnout this year. If so, we should see a considerably higher percentage of eligible Hispanic voters turning out than in 2012.

During early voting, the Latino surge prediction appeared to be coming true—and it indicated victory for Clinton. Nate Cohn of the New York Times’ Upshot wrote that, this year, there really was a surge: “Early voting data unequivocally indicates that Hillary Clinton will benefit from a long awaited surge in Hispanic turnout, vastly exceeding the Hispanic turnout from four years ago.” He based this assertion on some striking data from states like Florida, where self-identified Hispanic voters made up 15% of the early vote (compared to 12% of the final electorate in 2012), and where 36% of Hispanic early voters did not vote in 2012. Similar things seemed to be happening in Nevada and Texas.

Was this trend continued into Election Day turnout? And did the apparent surge really manifest in an actual turnout gain over 2012?

To answer those questions, we will eventually be able to consult voter files (which record registered voters and whether they vote in each election, and can be used to estimate demographic turnout even if they don’t record racial identity). In the meantime, we would like to be able to approximate from the national Exit Poll data, but we can’t.

One of the biggest problems with the Exit Poll is that it probably doesn’t do a good job of accurately polling people of color. This year, there are persistent questions about the Hispanic vote: according to the Exit Poll, 29% of Hispanic voters went for Trump, but groups like the polling firm Latino Decisions have cried foul:

“the national polling miss was only around 1-2% compared to what the popular vote margin will eventually be. These Latino numbers are off by 10-15%. That requires a plausible explanation, and secret support for a man who described Latinos as rapists and criminals does not pass the sniff test. …We suggest that if the Exit Poll numbers seem inexplicable, maybe they are wrong.”

One reason for this discrepancy may be that the exit poll wasn’t conducted in many areas that are predominantly Hispanic. The same is true for predominantly African American areas. In fact, Edison has stated quite clearly that its poll

“is not designed to yield very reliable estimates of the characteristics of small, geographically clustered demographic groups. …If we want to improve the National Exit Poll estimate for Hispanic vote (or Asian vote, Jewish vote or Mormon vote, etc.) we would either need to drastically increase the number of precincts in the National Sample or oversample the number of Hispanic precincts.”

Add to this the fact that the exit poll (and most national polls) are rarely conducted in Spanish, and we have a real problem.

The co-founders of Latino Decisions offered an alternative on the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog, basing their analysis on LD’s random, representative, and bilingual polling. Barreto and Sanchez argue that their results “differ significantly from those of exit polls and, from a social science perspective, are more accurate and reliable.”

They found that, by their best estimates, somewhere between 13.1 and 14.7 million Latinos cast ballots in the 2016 election, a “significant increase from the 11.2 million Latino votes cast in 2012.” How significant? If turnout was closer to the lower number this year, it’s about a 2-point increase. But if it’s closer to the higher number, it’s a nearly 8-point increase. I’d call that a surge.

The Democratic Party must try to (re)capture the white working class vote

After such a devastating loss, there has been and will continue to be a lot of soul-searching in the Democratic Party. Some prominent figures, such as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, have pushed the narrative that the Dems have lost their blue-collar soul, and must move toward the economic left to recapture the white working class who went for Trump is such large numbers. They both have tickets on the “economic anxiety” train.

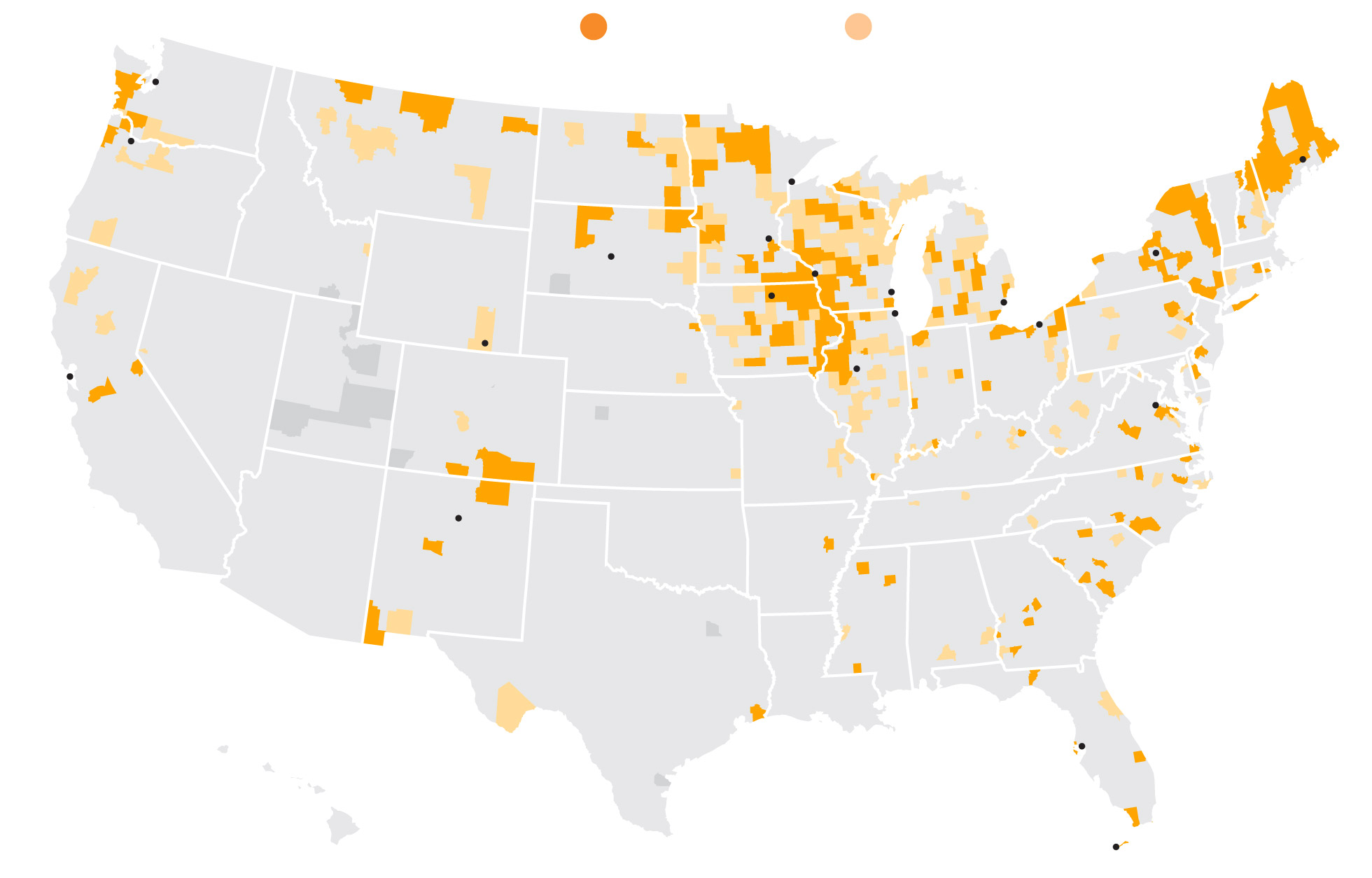

If the Democrats had lost white working class (WWC) voters in this election, we would expect to see counties that flipped from Obama to Trump to be WWC counties. We do see that. According to a Washington Post analysis, “On average, the counties that voted for Obama twice and then flipped to support Trump were 81 percent white. Obama strongholds that supported Clinton were just 55 percent white. There was also an education gap, with Trump pulling more support from counties with more voters with only a high school education. In Trump’s counties, 36 percent of voters had no college education, on average. In the consistently Democratic counties, only 28 percent of voters were not college educated.”

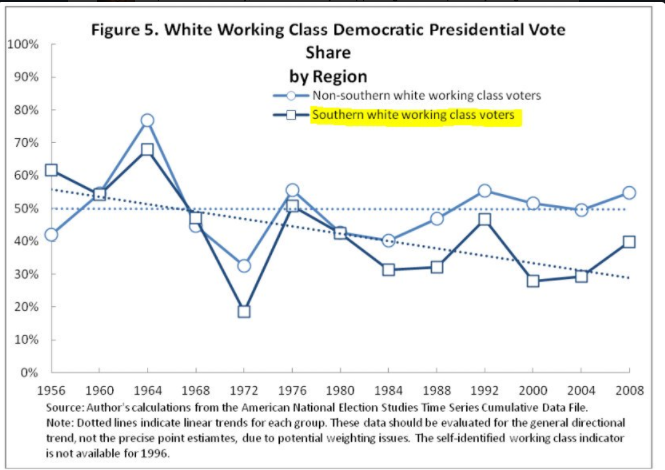

But, per Elisabeth Jacobs of the Brookings Institution, white working class voters in the South have been moving away from the Democratic Party for decades. This shift is no accident: it results, in large part, from a deliberate divide-and-conquer Republican approach known as the Southern Strategy, which was introduced under Nixon and continued under Reagan and both Bush presidencies. (You can find its segregationist origins in 1948, when Strom Thurman ran as a spoiler candidate to defy Truman’s civil rights platform.)

While Sanders made a strong bid for white working class voters reuniting around shared (liberal) economic concerns, for the most part Southern white voters left the Democratic Party a long time ago.

The Democratic Party must move left to activate the New American Majority

Let’s turn to the other major dimension of the Democratic party for a moment. Many voters of color felt betrayed by the Clinton campaign—and Democrats more broadly—in the 2016 race. Following eight years of the first Black president, it was disappointing to many voters of color for the party to not only nominate an establishment centrist white candidate, but for her to then choose a running mate who was also white (and perceived as the safe choice). Then there was Clinton’s legacy of supporting mass incarceration policies in the 1990s that have sent many people of color to prison; her support for “welfare reform;” her late-to-the-party turnaround on same-sex marriage; her hawkishness on numerous wars and surveillance; her embrace of “countering violent extremism” programs and framing Muslim Americans as primarily partners in fighting terrorism.

With the failure of the Clinton strategy—and the triumph of a racist, xenophobic, sexist candidate—some argue that the Democratic Party must “center the fears and concerns of nonwhite Americans.” Per Ramachandran, this would also include making feminist concerns a central tenet of the party platform. The New American Majority, sometimes also called the Rising American Electorate, is a fictional coalition of young voters, voters of color, and unmarried female voters; it is this “new majority” that some argue the Democrats should be focusing on winning.

The narrative here is twofold. First is a moral argument: the Democrats are (since the Civil Rights Act) the defenders of gender, racial, and underprivileged justice. This party has a responsibility to these voters to make the concerns of young people, people of color, and women central to its platform once again.

Second is a strategic argument: the New American Majority (NAM) is so called because it is where electoral majorities will be found in the future. That is, the Democrats should read the Census tea leaves and start consolidating this coalition now, given their existing strong base of support with these voters.

So which is it?

There is an important strategic question here. The Democratic Party is being pulled in somewhat competing directions, and it will be hard (though not impossible) to chart a winning strategy that captures both white working class voters and the New American Majority.

For a few reasons, people of color tend to vote in lower numbers than white voters and less habitually—that is, these voters tend to “surge” in presidential years and “ebb” in low-interest/midterm elections. One of the reasons is that there are historical and present-day impediments to voting that white voters simply do not experience. These depress turnout and make habitual voting much less likely in communities of color.

But given that these barriers are, if anything, increasing rather than falling away, we probably can’t expect non-white voters to turn out in high enough numbers to win a Democratic majority in near-future elections. So the Democratic Party must find a way to activate its white base and win more white habitual voters—if only to grab enough power to break down those barriers to voters of color.

Focusing on the New American Majority is also a strategy that will work better in some electoral cases than others. The national popular vote, for example, will be increasingly driven by this “coalition” in the next few elections; but winning the Electoral College depends more on a few key states and counties where the NAM is less of a majority. By the same token, the NAM has majority potential in some states more than others, and in some districts more than others, making this a viable strategy for winning House races, but not necessarily Senate.

Why this matters

ReThink Media and many of our partner organizations are (c)(3) non-profit organizations, so we do not work directly with or in support of any political party or candidate. However, having effective political opposition to the party in power is an important part of our checks-and-balances system. What’s more, it’s crucial that our political system work for all Americans, which includes our two major parties adequately striving to represent the broad spectrum of identities and political ideologies in our political landscape.

More concretely, we know that partisanship is one of the most predictive elements of political decision-making—especially when people encounter a new issue. How each party shapes and reshapes itself has enormous bearing on all manner of public opinion in the near and far future.

Coming up…

In the next few weeks we’ll take a look at the failure of the polling industry to accurately predict this election, the role the media played in the outcome, and some “what if” scenarios.

In the meantime, how is your organization planning to widen its base and identify new partners? Tweet to us @rethink_media and let us know.