Post-Election Data Download: Narratives About Republicans

This post is the second in a series that will examine the election and attempt to answer questions we have been asking internally and fielding from friends, colleagues, and allies. Please don’t hesitate to contact us with additional questions or input.

This week, we’re looking at a few of the dominant narratives you may be hearing about the election. Previously, we asked whether the Trump vote was motivated by racism or by economic anxiety. Today, we address a couple of narratives about Republican voting behavior in this year’s election.

There was a “Trump surge” on Election Day

With a strong #NeverTrump movement and many establishment Republicans publicly repudiating Trump, it seemed that the GOP was experiencing a loss-inducing schism up until November 8. FiveThirtyEight published a long examination of how “racial and cultural resentment have replaced the party’s small government ethos” titled “The End of A Republican Party” all the way back in July. In this piece, Clare Malone called Trump “a one-man crisis for the GOP.” Several months later, in the staff’s weekly Politics Chat, Julia Azari compared the leadership crisis currently plaguing the Republicans to the Watergate scandal, while the party’s coalition crisis was more akin to the Democrats around 1856, “in the sense [that] the racist vote is always a bloc for either party. Until the 1960s, it was the Democrats. Now, the Republicans are contending with it.”

Yet, in the end, Trump prevailed—as did the Republican Party as a whole. How could this be?

One explanation for the win is that Republicans “came home” on Election Day. NPR political reporter Sarah McCammon reported on November 2 that “Republican and Democratic voters tend to come home” and implied that this was beginning to happen on both sides. Her colleague Mara Liasson said in an interview that FBI Director James Comey’s letter “accelerated Republicans coming home to Trump [and] delayed Democrats coming home.” Both reporters, and their colleague Dominic Montanaro, discussed this phenomenon several times on the NPR Politics Podcast.

Essentially, this would mean that many #NeverTrump voters abandoned their posts and ultimately decided to vote with their party rather than sitting out the presidential election or voting for another candidate. Since voters tend to make their choice based on party first, and other factors second, this explanation makes sense: it takes quite a lot to break a voter’s ties to his or her party. It is likely also the case that many Republican voters’ longstanding dislike and intense distrust of Hillary Clinton (reinforced by years of negative framing) simply proved too high a hurdle for many Republicans who may have flirted with a #NeverTrump position.

On the other hand, there is the narrative of a “Trump surge.” This would mean that—like a Latino surge—a larger-than-usual number of voters turned out to vote for Trump. Republicans tend to be more habitual voters than Democrats, so a Trump surge could look like many more Republicans than usual turning out or it could look like a large number of non-habitual voters turning out to vote for Trump and thus shoring up a lack of support from more establishment Republicans. Since we know from turnout numbers

that Republican turnout wasn’t especially high this year, a Trump surge would have to look like the second picture.

Did the Trump campaign convince a lot of non-voters to turn out this time? Yes, maybe. David Leonhardt suggests there was a Trump surge in some places, and that his activating non-voters from 2012 helped more than flipping Obama voters from 2012. He writes that, “In the simplest terms, Republican turnout seems to have surged this year, while Democratic turnout stagnated. The Republican surge is easiest to see in those same heartland states that flipped the election.” An analysis by YouGov’s Douglas Rivers looks at five “switch” states and Minnesota, which nearly went to Trump. In each of these states, “turnout rose more in conservative areas than in liberal ones. That pattern, obviously, cannot be explained by vote-switching among the white working class.” For example, in Pennsylvania’s solidly Republican southern strip, turnout rose almost 10 percent relative to 2012; but in the big cities and labor union stronghold of Allentown, turnout rose only a few percent.

According to YouGov’s proprietary polling, “For every one voter nationwide who reported having voted for Obama in 2012 and Trump in 2016, at least five people voted for Trump after not having voted four years ago.” (my emphasis) Clinton didn’t gain nearly as many 2012 nonvoters. “On net, “Rivers says, “Trump’s gains among nonvoters mattered more than his gains from vote switchers.”

Unfortunately, we won’t be able to answer this question definitively for a few more months, at least, because we don’t have much data on individual voters and their motivations.

Trump was the change candidate, just like Obama in 2008

This narrative is the hardest for Democrats to swallow, particularly given how reprehensible the Trump rhetoric was toward anyone who wasn’t a white man (and for a large number of white men, as well), and the regressive nature of his slogan, “Make America Great Again.” Yet, it seems that white voters were willing to overlook quite a lot—not just in terms of bigoted language and policy proposals, but also in terms of financial scandals, flouted traditions, and an off-again relationship with truth—for the promise of a new (old) order.

From the perspective of people who feel left behind, David Weigel explains, “Washington stumbled and failed and offered nothing; Trump offered brisk if unspecified change.” Many of these voters have been frustrated with the Democratic Party moving away from them (something I’ll address below), and Trump’s persona as a Washington outsider so wealthy he didn’t need to compromise with anyone appealed to many. He promised he could bust through the gridlock in Congress.

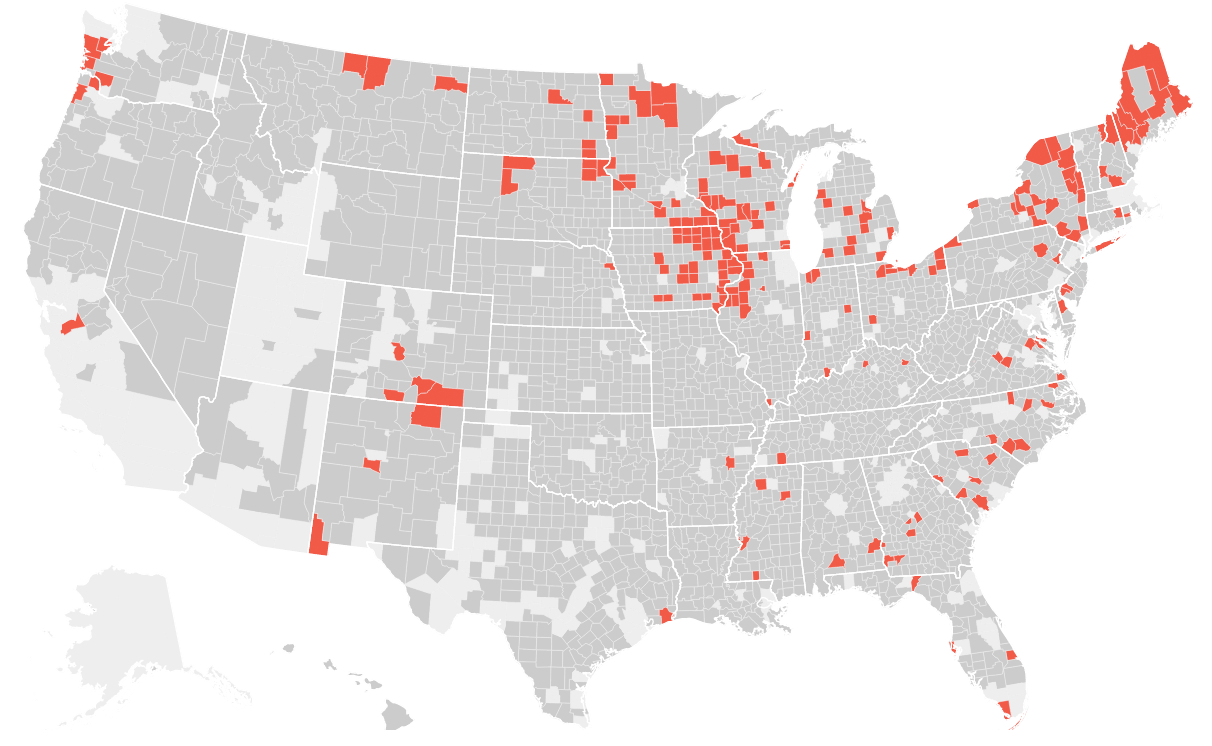

Certainly there were many counties that went for Obama in 2008, but for Trump in 2016. One-third (209) of the 676 counties that supported Obama in both his elections flipped for Trump, and nearly all (194) of the 207 counties that went for Obama in 2008 or 2012 went for Trump.

These flips were not mirrored on Clinton’s side, a serious failure of the campaign. Because it was a skewed phenomenon, it played a part in flipping Iowa, Wisconsin, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Florida for the Republicans. The Washington Post has a nice map illustrating where the majority of these counties clustered.

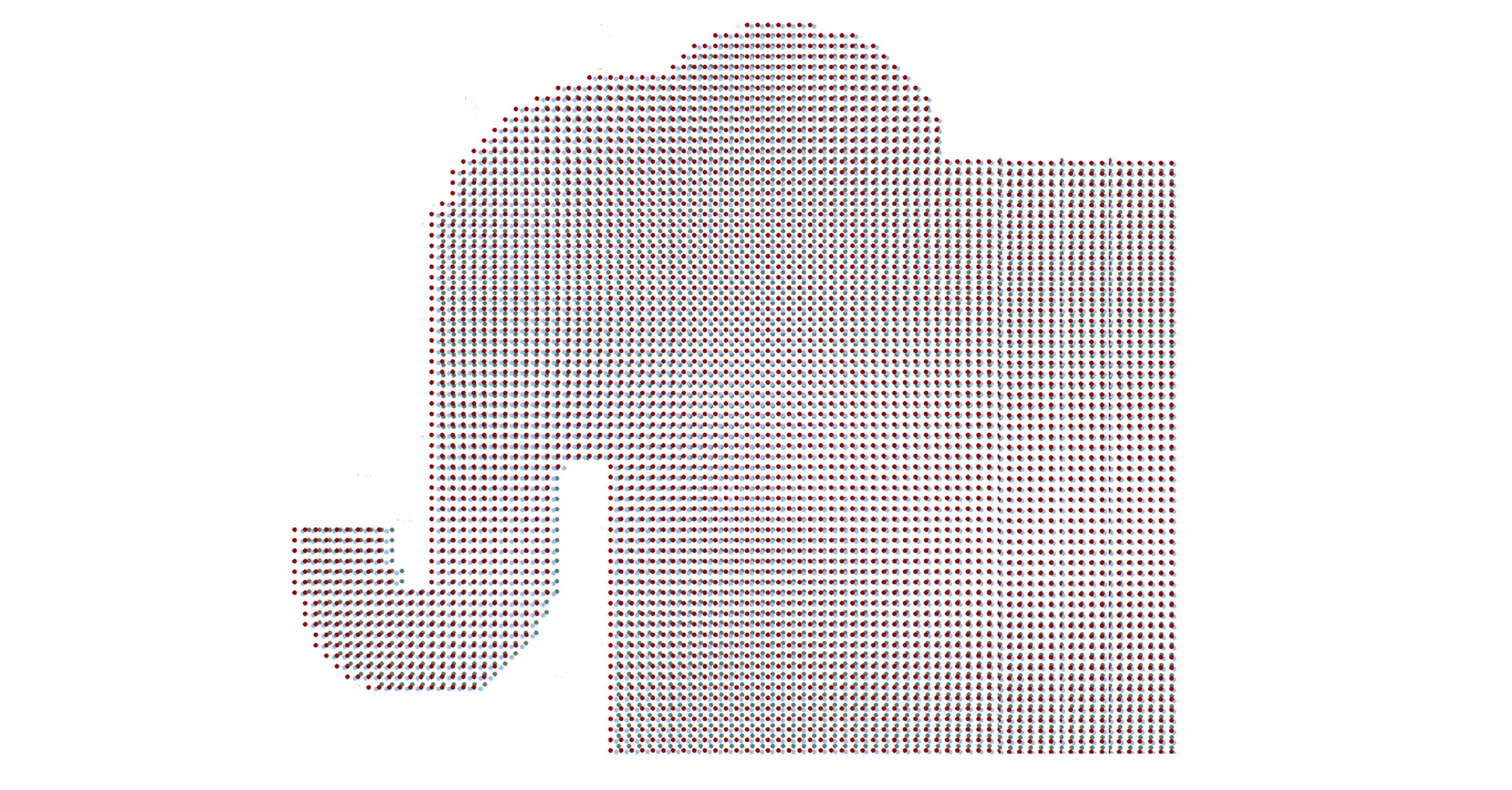

NPR created paired maps that really show how lopsided the flips were. Counties that voted more Republican than in 2012 (in dark grey), and that fully flipped Republican (in red):

Counties that voted more Democratic than in 2012 (in dark grey), and that fully flipped Democratic (in red):

Polling indicates that Trump voters were hoping for change…but not necessarily expecting it. For example, a poll of white working class Americans by The Atlantic and PRRI shows that “Six in ten (60%) Republicans and 66% of Trump voters believe the election represented the last opportunity to arrest America’s decline, while only 29% of Democrats and 22% of Clinton voters embrace this view.” Yet only about half of white working class Trump voters—and about a third of WWC voters overall—expect the quality of life in their local community to get better now that Trump has won. The Atlantic quotes a traditionally Democratic voter in Ohio who went for Trump this time: “I doubt very much that he’s going to do much of anything … I just wanted to see if there could be a change … I didn’t want the same thing that we’ve had for eight years. And I think that’s what was going to happen.”

Why it matters

There is a serious question among progressive advocates about whether Trump voters are “lost” forever. Nothing can really get done in the United States—by design—without reaching across political divides and working together toward compromise, so it’s important to figure out whether progressives and their allies on key issues simply have fewer strategic possibilities available to them now.

I don’t think so. What is clear is that voters are hungry for change and are willing to shout very loud to get it. Yet these voters are also not as optimistic that Trump will bring that change as we might assume. Indeed, many are already deeply disappointed and disenchanted. There will be plenty of opportunities to reach Trump voters and work with their representatives in government, particularly as the Trump administration is already contradicting campaign promises to “drain the swamp.” Advocacy messaging going forward should probably use “change” framing when trying to reach this audience.

What are some of the ways your organization is planning to engage Trump’s base, if at all? Will you embrace “change” messaging? Tweet to us @rethink_media.org and let us know.