How to Use Twitter to Correct a Journalist’s Coverage … Without Ruining Your Relationship

If you’ve been following along with our series on engaging reporters on Twitter, you already have updated your Twitter bio to look like an expert and know how to start building a relationship with journalists using Twitter.

This all comes in handy for those moments we dread: When we have to push back against a reporter’s coverage, provide more information, or make a correction.

They could be the friendliest, most well-intentioned reporters, people you talk with often and who regularly quote your experts. But it happens.

Keeping the following strategies in your back pocket will make it a little less nerve-racking to reach out to reporters and push for that clarification or correction – while keeping your relationship with the reporters intact.

Much of this strategy depends on the tone you take with the reporters and whether you engage them in a public or private fashion. Each approach evokes a different response from reporters. We’ll talk about a few examples of each.

You’ll note one thing that these examples have in common: They all came from Twitter accounts associated with an individual – not an organization. For pitching and relationship-building purposes, journalists tend to prefer that engagement come from spokespeople’s personal Twitter accounts. The engagement feels much more authentic that way, and less like an overt PR maneuver.

Public vs. Private

One factor in determining how a reporter receives criticism is whether it’s delivered publicly or in a private, direct message. There can be pros and cons with either strategy.

Sending a private, direct message

If the reporter is someone you know well and/or work with often, and if the detail that you hope to correct is of more modest importance, a private, direct message might be more appropriate than tweeting at the reporter publicly. This gives a helpful suggestion without putting the reporter in the public hot seat. He/she can simply make the correction and call it a day, with ego and reputation mostly intact.

This usually only works if the reporter follows you on Twitter and vice versa. Otherwise, Twitter won’t allow you to send a direct message. (The exception is if the reporter has turned on a Twitter setting that enables non-followers to send direct messages.)

Sending a public reply or @-tweet

If the reporter doesn’t follow you, but you’d like to push back softly, when you tweet at them, make sure their Twitter handle is first in your tweet and that the first character of your tweet is the @-symbol. For now, Twitter treats this as a reply and only shows this content to the people who follow both you AND the reporter, which is likely just a handful of people. (NOTE: Twitter is reportedly changing this soon.)

But this helps to bring the reporter’s attention to the correction without alerting all of his/her followers that there was an error. Ego and reputation are still pretty safe using this tactic. But again, consider your tone when sending a public tweet.

Sending a public tweet

If this is a reporter with a lot of followers and who tweeted something particularly problematic, which would be distributed to that universe of followers, a public correction could be useful. This makes it more likely that others following along in the Twitter conversation can see the pushback.

To do this, include the reporter’s Twitter handle in the tweet, but make sure the first character is anything BUT the @-symbol. This allows the tweet to be sent to all of your followers, as well as those monitoring that reporter on Twitter. This has the largest risk of harming the reporter’s ego and/or reputation, so just make sure that what you are saying is accurate and is delivered with the appropriate tone.

Watch that Tone

You can correct the same detail of a reporter’s coverage multiple ways – which all achieve the same result of sending a correction, but which can also be received differently by the reporter and affect your relationship going forward.

We will discuss a few options in tone that we have seen, as well as some of the pros and cons of using these tactics.

You can be really nice about it

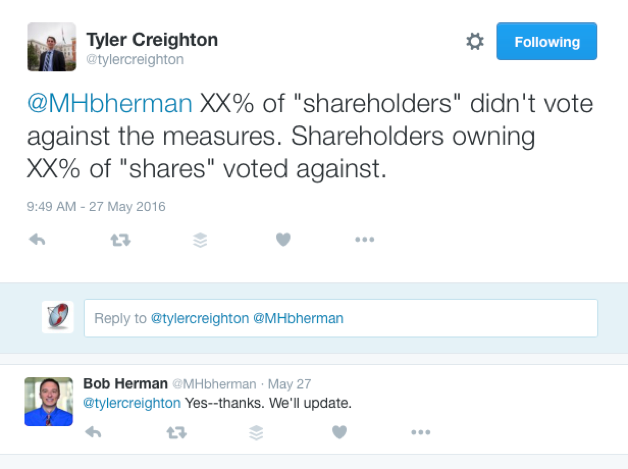

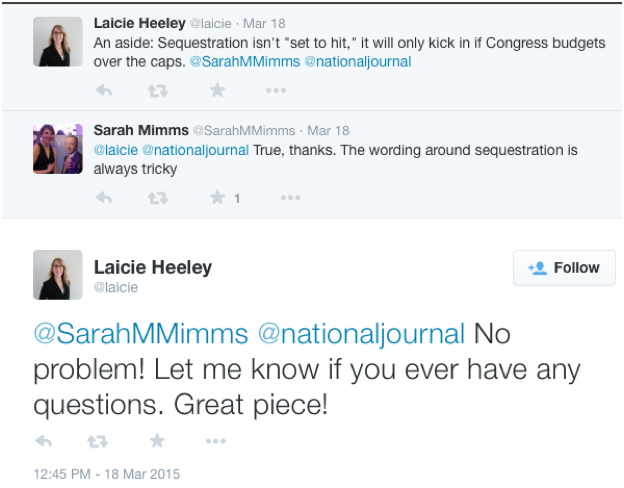

Above, Laicie Heeley with the Stimson Center makes a friendly, but pointed correction on terminology in Sarah Mimms’ National Journal article about sequestration. She follows it up with an offer to talk and compliments the piece still, despite the phrasing correction.

By phrasing her correction as “an aside,” Laicie is non-combative, just providing some helpful guidance to the story, which will help Sarah Mimms in her future reporting about sequestration.

And by offering to answer any future questions, Laicie invites the reporter to continue to contact her, making it more likely that Sarah will contact Laicie as a source who understands the technicalities of complicated government programs.

And by finishing the tweet with, “Great piece!” Laicie leaves the reporter feeling good, helping to build a rapport and ensure that the two have a good relationship going forward.

You can provide more context

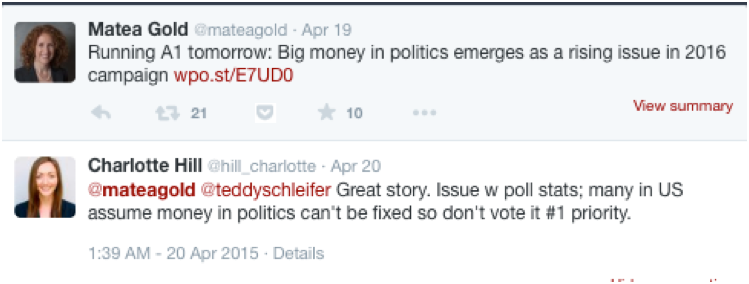

Above, Charlotte Hill, of Represent.Us, tweets at Matea Gold of the Washington Post, complimenting the story, but offering context and a slight correction.

It is a friendly tweet, directed (publicly) just to the select few who follow both Charlotte AND Matea, but provides additional context as to why those polled hadn’t ranked money in politics as higher priority in the 2016 election.

Matea can choose to include that detail or not, but Charlotte offered that information in a non-combative, helpful manner. This shouldn’t hurt Matea and Charlotte’s relationship in the future.

You can have a sharp attention to detail

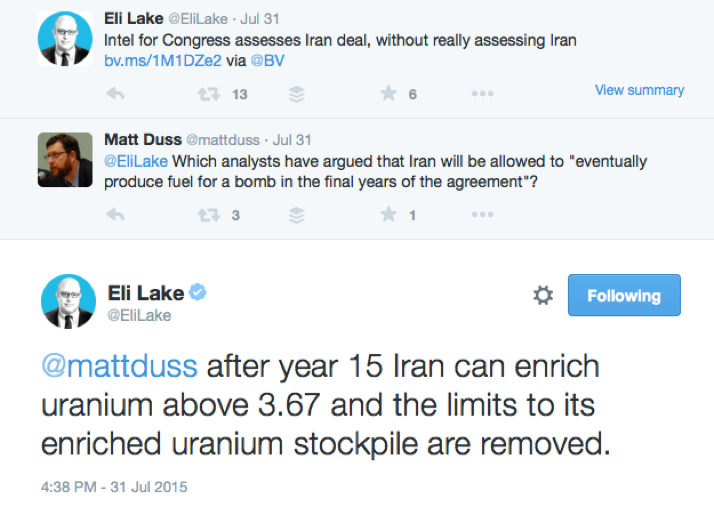

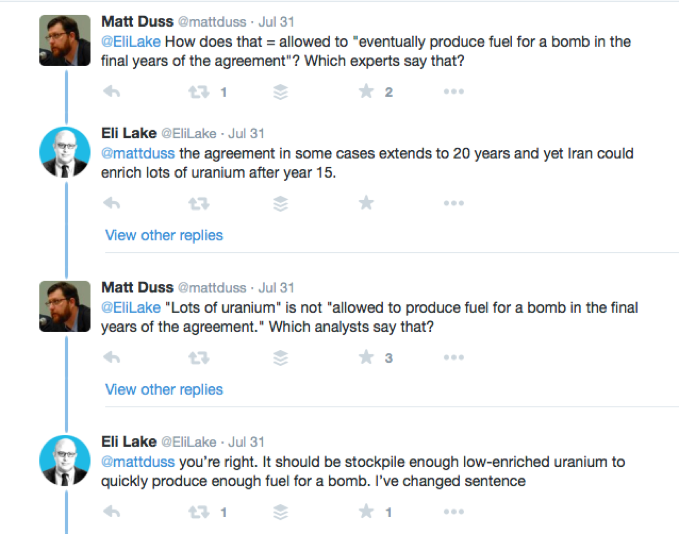

In this example, Matt Duss of the Foundation for Middle East Peace really dug in to details that Eli Lake of Bloomberg View reported about the Iran Deal. Which experts said that?

Unsatisfied with Eli’s response, Matt asked again, “Which analysts? How much uranium?”

Eventually, Eli backed down and said that Matt was right, and that he changed the sentence.

Matt followed up with a quick, polite thank you, ensuring that he doesn’t ruin his relationship with the reporter for future stories. He made substantive comments, was right, but didn’t gloat. He simply thanked Eli and moved on.

You can go for the jugular

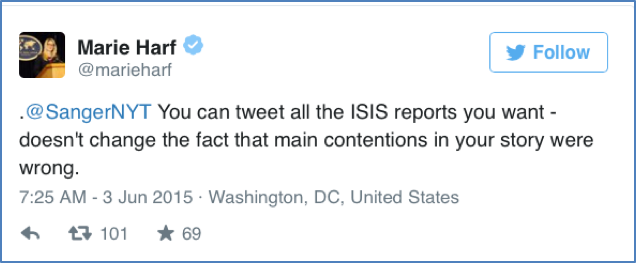

In June 2015, during the heat of the negotiations around the Iran nuclear deal, the New York Times’ David Sanger ran a story about how Iran’s nuclear stockpile had grown, an assertion that was complicating negotiations.

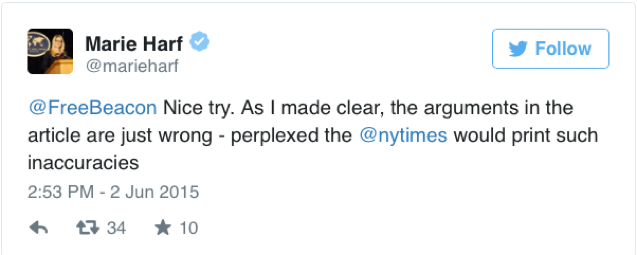

In response, State Department acting spokeswoman Marie Harf tweeted that she was “perplexed” about the Times report.

Harf’s comments won her a subtweet from Sanger, an infrequent tweeter.

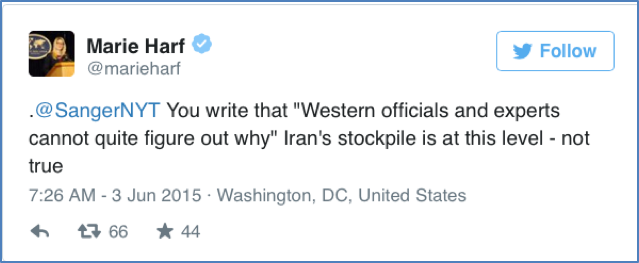

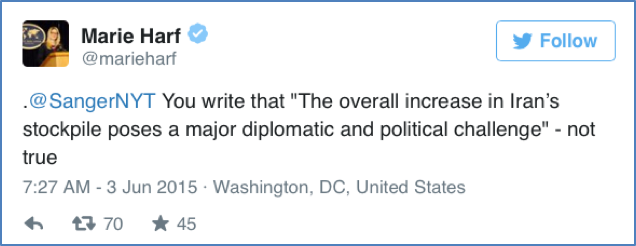

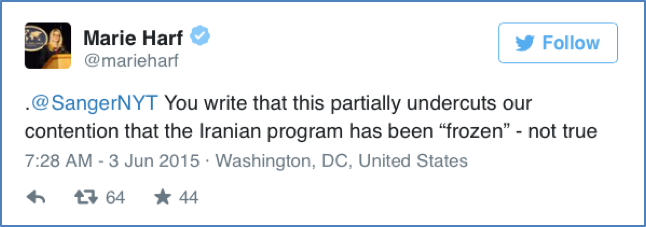

This is where the fun begins. Harf begins tweeting a line by line takedown of the article, pointing to all of its flaws.

Here are just a few of the tweets that Marie Harf sent about that NYT story.

Harf’s strategy generated a lot of media buzz, with articles appearing in CNN, Politico, the Wall Street Journal, Mediaite, and NBC News, among other outlets.

Her strategy also put a magnifying glass onto the details of a very technical part of the negotiation. For example, this Vox piece was all about “the real reason the State Department is Twitter fighting with the New York Times about Iran.”

It features an entire section on “How the Times got the technical issue right and its significance wrong,” going into specifics about low-enriched uranium and the specific levels that were being negotiated in the Iran Deal (pretty darn specific coverage).

In Harf’s case, this strategy worked and in no small part because of her relative power in the interaction. But it will not necessarily work for everyone and should be used very selectively.

If you are going to be as aggressive as Harf was in her takedown, please, please, please proceed with caution. Take a deep breath and make sure you want to say something (and think about how to say it); don’t just respond in the heat of the moment.

The more aggressive you act in your response, the greater the chances this could negatively affect your relationship with the reporter in the future.

While Harf was a little safer than most because the New York Times is always going to want a good source at the State Department, in our position as nonprofit communicators, it’s a bit more precarious.

Working in coalitions, there is little to stop a scorned reporter from just replacing coverage you might have gotten with a voice from another organization.

So, before you employ this tactic, it is best to double-check both with your communications director and your executive director, making sure you aren’t harming the organization’s relationship with that reporter or that outlet going forward.

Conclusion

Now that you have a few strategies and tactics in your back pocket, you may begin using Twitter to correct a reporter’s coverage. Just make sure you consider whether to do so publicly or privately, and what is the most appropriate tone to take.

What strategies have you tried, and how have they worked?

Have you seen any of these exchanges on Twitter that you think other ReThink Media members can learn from?

Tweet to us @rethink_media and let us know!